Tariff trouble.

Just two weeks ago, the U.S. government lifted tariffs on Mexico and Canada. So, it was a surprise last week when President Trump tweeted the United States would impose an escalating tariff on all goods imported from Mexico until the flow of migrants to the United States’ southern border stops.

The pending tariffs have potential to hurt both American and Mexican economies, reported The Economist. “Two-thirds of American imports from Mexico are between related parties, where one partner owns at least 10 percent of the other, so any tariff will cause problems along tightly integrated supply chains.”

In 2018, Mexico was the second largest supplier of imported goods to the United States. It provided 13.6 percent of U.S. imports. In addition, Mexico was the second largest importer of U.S. goods. The country took in 15.9 percent of overall U.S. exports, including machinery, electrical machinery, mineral fuels, vehicles, and plastics, according to the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

The new tariffs (a.k.a. import taxes) may increase costs for ordinary Americans. Last week, Liberty Street Economics explained the costs associated with Chinese tariffs:

“U.S. purchasers of imports from China must now pay the import tax in addition to the base price. Thus, if a firm (or consumer) is importing goods for $100 a unit from China, a 10 percent tariff will cause the domestic price to rise to $110 per unit…it is not a true cost for the U.S. economy because the money is simply transferred from buyers of imports to government coffers and thus could, in principle, be rebated.”

A different type of cost occurs when companies find new suppliers. For example, a company that chooses not to pay tariffs can buy goods elsewhere. They might choose to pay a Vietnamese firm $109 for a product rather than pay a Chinese firm $110 ($100 plus a 10 percent tariff). In this situation, the consumer pays a higher price and there is no tariff revenue that could be rebated. This is called a deadweight loss.

In total, Liberty Street Economics estimated the cost of 2018 tariffs on Chinese goods at $419 a year for the typical household ($132 in deadweight loss). The tariffs imposed in 2019 are expected to cost $831 a year ($620 in deadweight loss).

Liberty Street Economics did not estimate the potential consumer cost of new tariffs on Mexico.

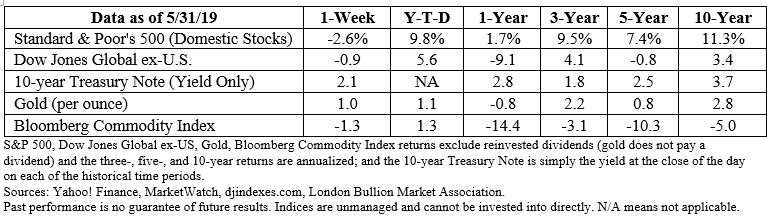

Major U.S. stock indices finished lower last week. Yields on U.S. Treasuries moved lower, too, suggesting investors may have been seeking safe havens.

By Kevin Theissen, Principal and Financial Advisor, HWC Financial, kevin@skygatefinancial.com